The Phrase "Mass Grave"

Today the UN reported on the discovery of many people deeply buried under the earth in Gaza. The dead people were in many cases naked and bound at the hands:

Disturbing reports continue to emerge about mass graves in Gaza in which Palestinian victims were reportedly found stripped naked with their hands tied, prompting renewed concerns about possible war crimes amid ongoing Israeli airstrikes, the UN human rights office, OHCHR, said on Tuesday.

The development follows the recovery of hundreds of bodies “buried deep in the ground and covered with waste” over the weekend at Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis, central Gaza, and at Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City in the north. A total of 283 bodies were recovered at Nasser Hospital, of which 42 were identified.

“Among the deceased were allegedly older people, women and wounded, while others were found tied with their hands…tied and stripped of their clothes,” said Ravina Shamdasani, spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

—Mass graves in Gaza show victims’ hands were tied, says UN rights office

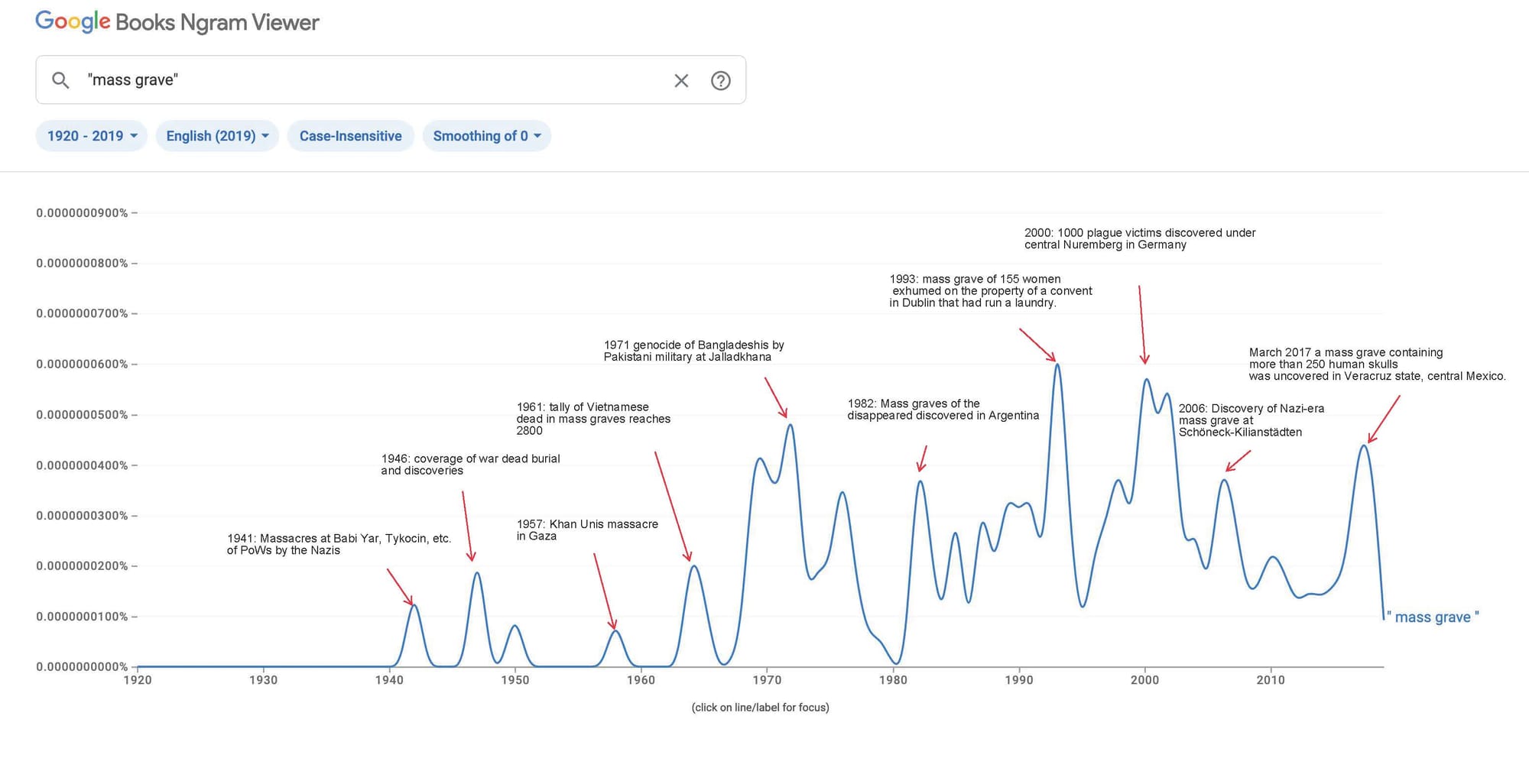

There are very few uses of the phrase "mass grave" in English-language publishing recorded by Google's Ngram viewer prior to 1941:

Although the close matches are grimly amusing. Mass: grave or light?

After 1941, the precise phrase "mass grave" enters mainstream English publishing from the corners of military reports. Observe the shift to coverage employing "mass grave" from the reporting of current events to the discovery of historic sites.

I'm not sure what people wrote before they wrote "mass grave." The word "bier" means the same thing, roughly—maybe it would be more detailed or more euphemistic, or somehow both. But there must have been a spike after this Ngram cuts off in 2019, when global deaths exploded at the start of the pandemic.

In May 2020 The Yale Review published an essay by Kathryn Lofton as part of their "Pandemic Files" series, titled "The Profound Horror of the Mass Grave."

It starts very beautifully:

When I was a child, my father hunted small game from the backdoor of our home, a small house surrounded by other houses and duplexes in a Midwestern city. He sometimes boiled the carcasses in the garage so he could reconstruct the animals’ skeletons, bleaching the bones and carefully wiring together the parts into lattice sculptures. Sometimes he had no plans for artistry, and just killed the animals to rid his yard of intrusion. These bodies he buried at the bases of trees and bushes at the border of the lawn in the darkest part of the night.

Once, when I was eight, I thought he had killed a tabby that occasionally accompanied me for a half-block as I walked to school. I waited until he went to the hardware store for something, maybe two weeks after the suspected crime, and I ran outside to dig up the freshest grave in the backyard. I exhumed the body with the intent to say a proper goodbye. Maybe too I wanted the measure of my father’s menace. The smell when I got to the animal’s body was so awful I threw up my lunchtime sandwich. I scrambled to rebury the creature and spray down my sick, reconstructing the scene so he would not guess at my investigations.

It wasn’t the tabby. Still, as I raked the dirt back over its body, I sang “Edelweiss” from The Sound of Music, which I decided was the most solemn song I knew.

Every child knows that when something dies it should receive a funeral.

When a news story suddenly affects the residents of the United States, particularly its major cities, its raw materials—the conceptual ingredients, the vocabulary in play, the writers who've claimed the topic—get a rethink. The main principle the drives content churn is relevance. So, old questions, even ones that feel simple or pointless to crunch through (ah, we're all using Zoom, what does that mean) get written about anyway and then circulated.

The Lofton essay is a good example of this phenomenon, whereby a well-written essay takes on the meaning of a phrase in its entirely, beginning with an alert that the consideration will be subjective with a personal memory and ending with a call to certainty about the right to funerals. Lofton continues on to the effect of witnessing mass death on the psyche when followed by no dedicated stage of mourning:

According to the experts, if we can provide funerals, we should provide funerals. It’s not logistics that keeps us from saying prayers or finding ways to gather ourselves socially. It is our society, or present lack thereof. It is hard to make a ritual when you don’t know what society you feel good about constituting.

I read a study about early medieval plague graves in Germany and find that, when people buried the victims, they observed the customary rites of burial. Plague bodies were dressed up carefully and given the same religious grave goods as those who died of other causes. The article is largely boring—DNA testing on soil samples, etc.—but then the authors get political, insisting that these medieval plague gravesites are not “mass graves”:

Usually, the term “mass grave” includes the perception of a certain way to conduct burials, like to bury the dead hastily, and with very minimalistic or no burial rites. Therefore, we would like to distinguish between “mass graves” and “multiple burials.” Both can be the physical or material expression of a plague outbreak and therefore a higher rate of mortality, but they show a very different way of handling the crisis by the contemporary society.

A very different way of handling. The difference is in whether you’re driven by haste or still observing the ceremonial rites. Mass graves exist when we want to move quickly; when we want to bury the mess without remark; when we can’t handle speaking aloud the society that made this loss on this scale.

We are running mass graves on Hart Island.

...

I think about whether we can make up rituals to make up for our ritual failure. After World War II, local civilian committees across Eastern Europe excavated mass graves. Sometimes they did so under the enforcing eye of occupying forces. Sometimes they did so voluntarily. I think about these acts of exhumation: about how the townspeople then individually buried the remains of the bodies. I wonder if any of them got sick, or cried late into the night about what they saw. I think about how we do small things—read a poem, say a prayer, leave a token—not because we aren’t collapsing, but to remember someone lost as someone particular.

I think of a program in Bernalillo County, New Mexico, that pays for burials and memorial services for people whose unidentified remains have been in county possession for at least two years. I think of a headstone they placed in the multiple burial site in 2012: “We grow afraid of what we might forget. We will find peace and value through community in knowing that we belong to each other.”

I think about what I could do. I think about the old shovel I dragged out to dig for the tabby, and I think about the shovel I have in my basement now. I think of how I could get in a canoe and paddle from New Haven to Hart Island. I think about how, even though I lack upper body strength or seafaring experience, I could ride the rip, passing Bridgeport and Norwalk and Port Chester on my right, with Long Island a long sliver on my left. I could paddle away, and find the island right at the juncture where Connecticut meets the Bronx, just before Long Island Sound becomes the East River.

I think I could do this. I think I should.

Here Lofton reaches towards the interesting idea that we shouldn't even use the term "mass grave" for the dead who passed unavoidably, or maybe she means for "us" in the here and now.

I do believe in the principle of content churn editing: Writers should be forced to start again from scratch in their articulation of even the most seemingly obvious ideas or cultural themes. It's rough when the news is pussy hat day but it's still worth it, because such essays always reveal something quite true about that exact moment.

So I think that the Lofton essay contains what we really think that a person deserves when it comes to mass burial, to people who experience "a higher rate of mortality." That the very words "mass grave" carry a kind of insult with them.

The Ngram also interests me because it suggests that the phrase is sort of recent, despite not being a recent phenomenon in human history, and because the uptick in its raw usage corresponds vaguely to an increase in descriptions of historical events, rather than reporting on those in the present day. It's a term that's so distancing that it works best on those who have been dead on a long time.

The Ngram also cuts off in 2019, right before the pandemic. Things will look very different in five years. The diagram will show an intersection of large numbers of global deaths with some number of news articles, I'm not sure how to guess whether it'll be relatively large or small, from today.

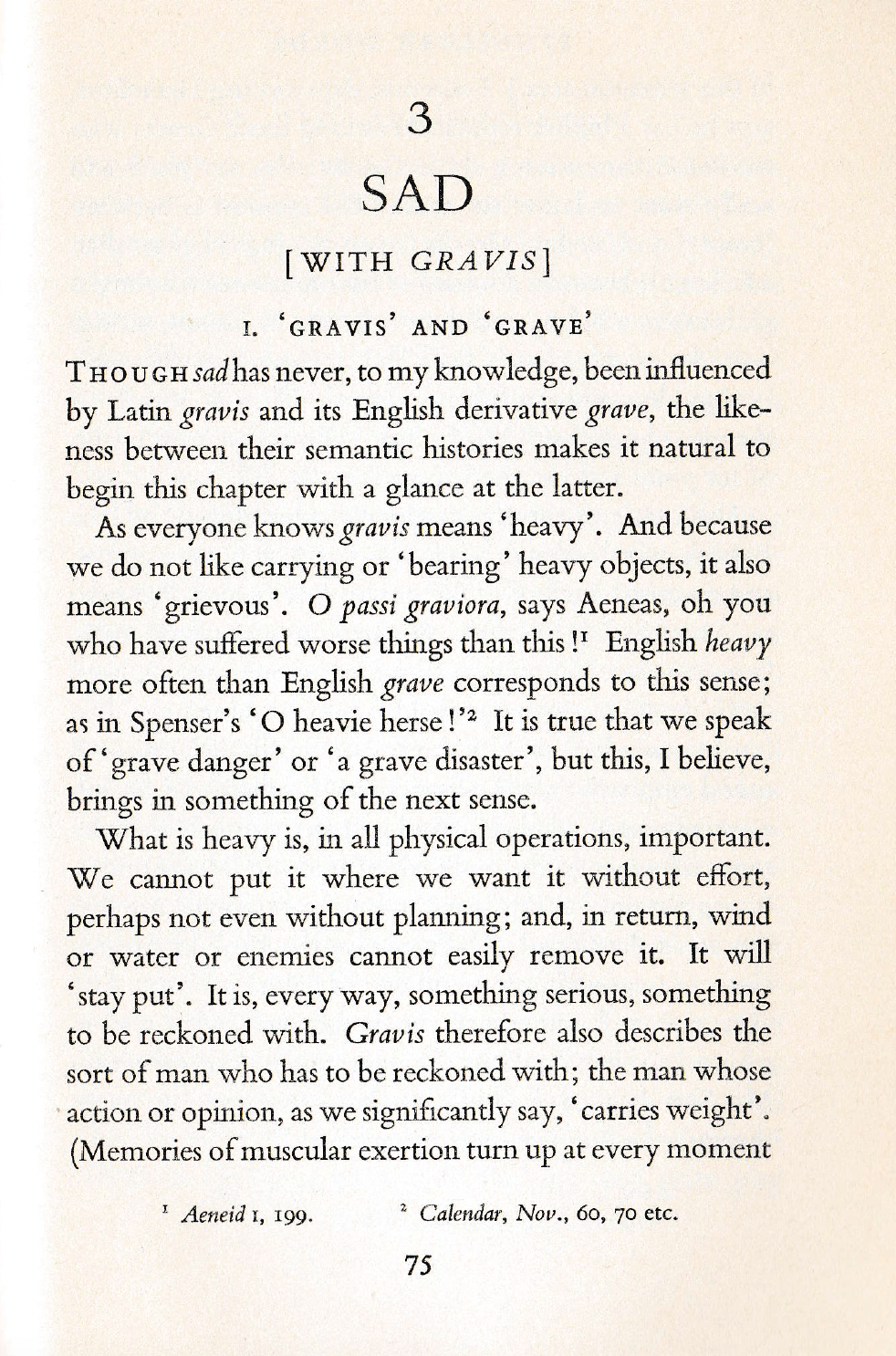

I'll leave you with CS Lewis on the relationship between the semantics of "grave" and "sad" in English (Studies in Words).

Comments ()