How Universities Grew State Powers

Less like a hedge fund, more like a government.

by Jack Marley-Payne

Universities in theory exist to provide post-secondary education. In practice, they do much else: develop property portfolios, amass stock holdings. But the nature of the contemporary American university is probably closer to a government than a hedge fund.

In her 2017 book of the same name, the political philosopher Elizabeth Anderson coined the term “private government” to describe the employee-employer relationship in the United States. The relationship, she explained, goes well beyond the economist’s definition of the exchange of labor and money and can cover all aspects of an employee’s life. An employer can monitor social media posts, hair styles, or support for favored political candidates, then legally punish a worker, including by the withdrawal of health care, leaving them without recourse. This type of power allows private employers to exert a level of control over workers’ lives traditionally reserved for the state.

Universities are among the largest and most powerful forms of private governance operating in the United States, functioning, as Davarian L. Baldwin puts it in In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower, as “quasi autonomous republics” in the territory surrounding their campuses. University statehood in many ways is a natural progression from the massive amount of power the US government delegates to owners of private property in general, but additionally exploiting their significant other advantages.

Universities are powerful employers, and not particularly scrupulous ones, operating in the knowledge that they are often virtually the only employer in town. More idiosyncratically, they wield power over people not in their employ.

First, they regulate the lives of students, who pay them. The university maintains their power over students through the fact that the student must graduate to get any value from the university—without a degree they may struggle to repay their accumulated debt. The threat of expulsion coerces a student to endure unpleasant and unfair conditions until they get their degree—NYU faculty recently wrote that student disciplinary proceedings amounted to “extracting coerced confessions” that asked, implicitly, “Have you reeducated yourself?”

Second, universities control residents who just happen to be living in their vicinity and have not willingly entered into any contract with the institution. They hold power not just over people but over a territory, functioning as a cross between a Victorian company town—proprietary currency included—and a principality within the Holy Roman Empire.

Universities maintain their territories through three chief strategies: ownership and control of property; wielding of force through campus security and police; and controlling the production and distribution resources through manipulation of their virtually unchecked tax-exempt status

Land

Elite universities need property for one clear key reason: To teach in. But many own a great deal of property outside the “campus.”

Such universities exert control over a contiguous area, determining social and material conditions for the entire surrounding region.

Columbia and NYU, the biggest landlords in Manhattan, act with entitlement over their patch of the city. As Baldwin notes, many local New Yorkers questioned the public benefit of massive expansion plans for the NYU and Columbia campuses proposed over the 2010’s, but “local residents and politicians said that the universities bought off government agencies, disbanded advisory councils, sidestepped community boards, and breached long-standing policy agreements.” Meanwhile, separate “private entities scrambled to reshape the neighborhood to provide campus amenities.” Developers flocked to chase the “greater profits of upscale student units over the Local needs for affordable housing.” In these areas, Baldwin observes, “university interests have become the public interest.”

These processes displace long-time residents in areas like Harlem or the South Side of Chicago, . Administrations maintain strong diplomatic relations with various branches of the US government to influence zoning rules and other policies that affect their land. The University of Chicago, for example, was reported by Eddie Cole to have actively lobbied to maintain segregated housing, stating “we cannot operate in slums.”

Force

As well as owning the land, universities control it through legalized coercive force, via campus police. As of 2015, 75 percent of higher education institutions across the US had sworn and armed police officers. Melinda Anderson notes, in her 2015 article, that these officers have all the authority of municipal police without being required to provide public reporting on their actions; instead, they report to higher-ups in the university, making them virtually immune to voter accountability. These police patrol campus but also the surrounding residential blocks in order to maintain a buffer zone for the campus, which Baldwin dubs a “two-tiered system of policing. A student and a community member can be accused of the same infraction, but the former meets with the dean, and the latter is shuttled through the criminal justice system.”

Regular police in the US are in theory answerable to the population and to their elected representatives, even if, in practice, they rarely give such answers. Campus police, on the other hand, are explicitly answerable to one social group while forcefully ruling over another. This is a colonial model of policing.

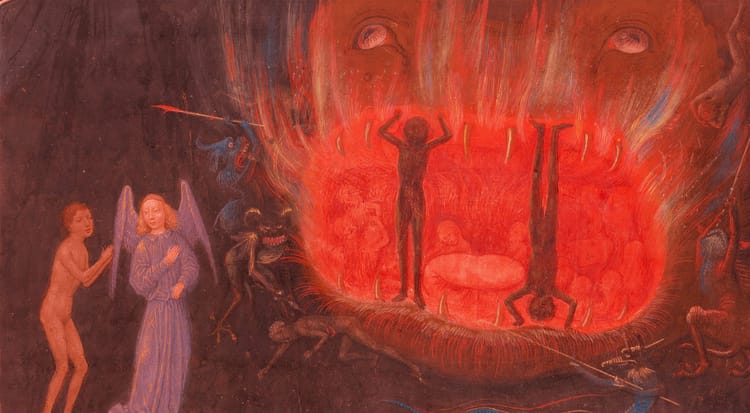

As Gary Haugen and Victor Boustros put it in their 2015 book, The Locust Effect, the “purpose and priority of this colonial model of policing would not be to protect the common citizenry from violence and crime,” but rather to “protect the colonial state and its narrow interests and beneficiaries from the common citizenry.” To do this protecting, these police “suppress riots and mobs. They guard expensive people and facilities. And they beat down disruptive challenges to the political regime.” See:

City University of NY public safety officer just said “I support killing all you guys” to a group of students who walked out of the graduation at the College of Staten Island. pic.twitter.com/CT0pOqAHiV

— Hebh Jamal (@hebh_jamal) May 23, 2024

University administrators defend these practices by arguing their first priority must be student safety. They do not take a democratic view as to which students’ safety counts, and those who do threaten the university leadership are treated like dissidents in any authoritarian regime. The university line also explicitly classifies local residents as second class citizens, subject to legalized force that does not act even nominally in their interests.

Tax and distribution

Compounding all of this is universities’ tax-exempt status. The theory behind the tax exemption is that universities are performing a public good—providing people with an education which they will go on to use to benefit society—that should be encouraged. However, that is far from all a university does and the tax-exemption applies to everything from rental income on property to interest on their multi-billion-dollar endowments.

The snowball effect of tax exempt status for universities can be seen in the ability those institutions gain to avoid property tax. That saving facilitates a greater return on their real estate, so they can buy more property, driving up prices and pushing out everyone else, while their avoidance of capital gains and gift taxes allows their endowment to grow so that they have an ever-bigger weight in the financial world, thereby expanding their policing budget.

Another particularly noteworthy area is patent income, by means of which research can be turned into revenue. Again, this is an area where universities have taken power away from the government. Much research is government-funded, and it used to be that results based on public funding had to remain in the public domain. Universities, however, successfully lobbied for the Bayh-Dole act, which allowed them to retain exclusive intellectual property rights on publicly funded discoveries. Here’s Baldwin again, on Bayh-Dole:

After passing Bayh-Dole, research universities jumped at the chance to secure patent and licensing arrangements with corporate sponsors… For example, Arizona State (ASU) has nurtured a voracious appetite for capturing the profits that might come from commercializing academic research… by connecting global business partners with ASU for a range of services from leasing office space and licensing research technology to providing student labor. (Baldwin 2021, pp. 42-43)

These operations are far from a matter of academic research, even of an applied and practically focused nature. Universities have absorbed large segments of the private sector, taking a range of activities that are traditionally for profit and bringing them inside their tax-exempt umbrella.

Most notoriously, this includes weapons manufacturers—many universities have a ‘Lockheed Martin Day’—but also pharmaceuticals, computing, and most other technologically involved sectors.

As universities don’t pay tax to an external body, they are free to take and redistribute resources from their many endeavors as they see fit, essentially operating an internal system of taxation and spending. Their justification is that this money can be used to fund scholarships for needy students, which is implausible insofar as the scale of scholarships does not at all line up with the scale of the operations. Further, it’s not clear why universities should be granted the authority to undertake these redistributive efforts outside of democratic oversight.

Statehood

A state is often treated as interchangeable with a nation, making it hard to see how businesses and universities could qualify. But the unitary nation-state is a relatively modern idea while the powers of state have existed in many forms throughout history, often with multiple acting upon a person or territory simultaneously.

A state, as Charles Tilly argues, wields legitimate (i.e., legal) force, maintains internal order, adjudicates disputes, and manages distribution and production of resources. Democracy is the modern justification for subjecting people to these powers. Each citizen is in theory an equal participant in the process that shapes the rules one is bound to.

The university is not remotely democratic. First, the institution explicitly disregards the interests of many of those it rules over—local residents and lower-level employees. Further, even those it is meant to be serving, students and faculty, have very little say in its decision making. The university power structure—president, provost, board of trustees—and the rules about who can appoint and depose whom, is opaque in the extreme, but, in general, the balance of power rests with existing trustees and wealthy alumni.

If you were to look at Columbia’s board of trustees and try to guess based on their careers what type of institution they were governing, you’d be unlikely to hit upon teaching undergraduates. The bulk is comprised of elites from finance, real estate, the legal world, and politics .

What do these people offer to Columbia? Access to power across a range of the most important axes in the US.

This makes perfect sense if the university is viewed as a state. The board is well suited to the goal of maintaining power within its current territory and amassing more wherever possible.

In turn, the university offers trustees a way to translate their wealth into a level of power even the greatest personal fortune cannot provide. Trustees are unpaid, but most have already achieved a level of wealth such that they are not looking to acquire any more spending money, but to find ways to shape society as they see fit. Universities offer exactly that. Colleges like MIT were an essential part of the move to destroy manufacturing guilds and permanently reshape US class relations. University governorship provides an opportunity to rule without the trouble of winning a public election.

When worrying about the state of democracy, the focus is typically on the US government and its grave failings. Underlying much of the failure, though, is that private entities operating as brazen oligarchies, have seized so many governmental powers.

Make the university a failed state.

Comments ()