"I Called Him 'My Queer Friend in Gaza'"

An interview with Afeef Nessouli, contributor to Pinko's new zine Queer Palestine.

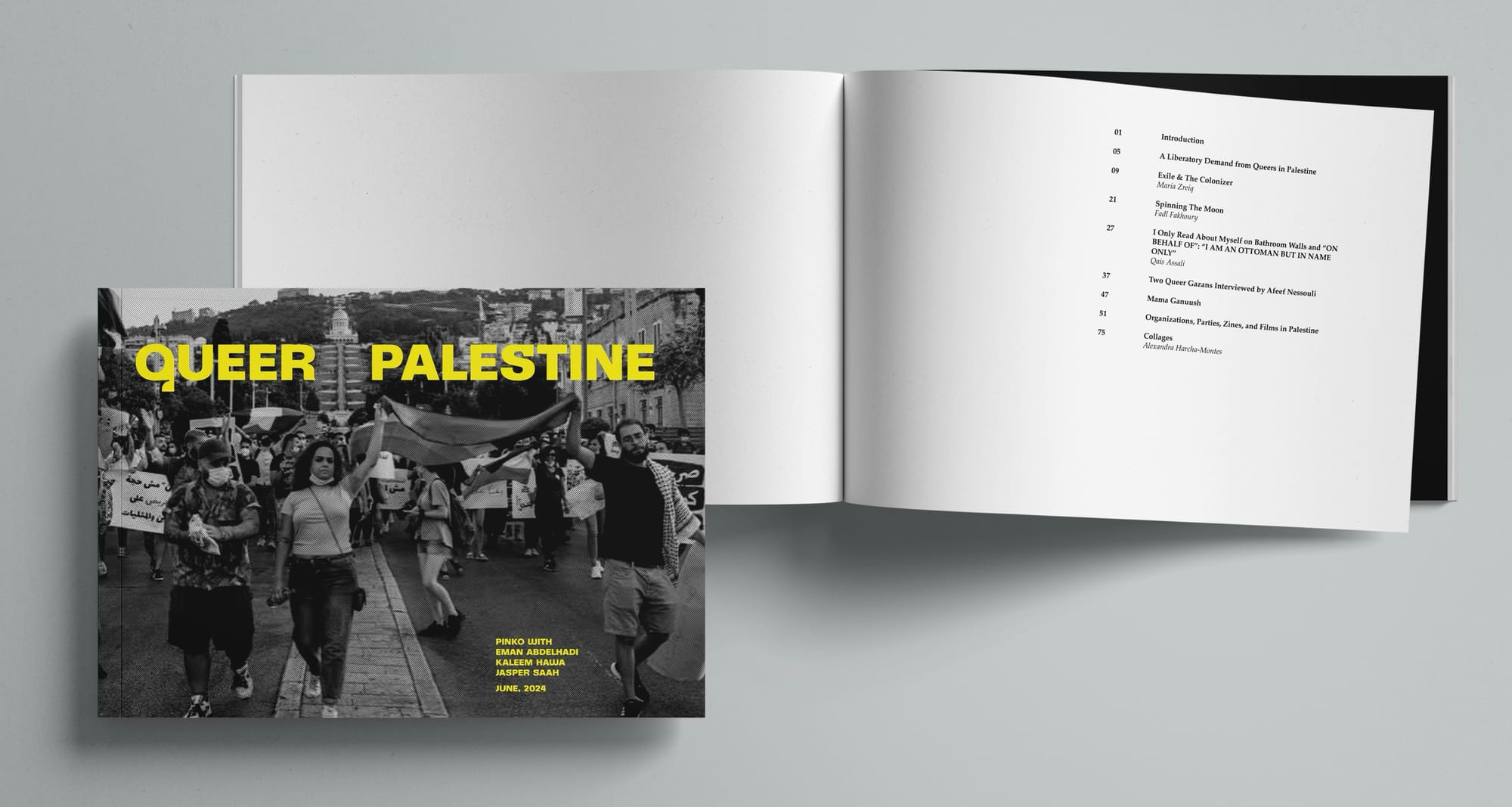

Pinko, "a collective for thinking gay communism together," recently released an extraordinary zine called Queer Palestine. For it, the collective invited queer Palestinians to "curate a small archive of queer Palestinian life." Among its aims are to counter "the annihilatory Zionist drive targeting Palestinian life in general, which ratified itself perversely in the name of its queers," and to "host a record of that which was said to be a contradiction in terms."

Below, The Stopgap speaks with Afeef Nessouli, who coordinated written contributions from two queer Palestinian individuals to the zine.

All proceeds from the book will go to direct relief efforts for contributors on the ground in Gaza.

Purchase your copy of Queer Palestine here.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jo Livingstone: Thank you so much for speaking with me, Afeef. I really appreciate it. Could you start by telling me a little bit about yourself and your career?

Afeef Nessouli: Yes. So, I'm a journalist and a producer. I've worked for a bunch of different kinds of outlets but went out on my own about a year ago. I was at the Wall Street Journal and Spotify, where they had a daily news podcast, and before then I was in Beirut doing a fellowship with this Google podcast program. I was covering the revolution. And then before that I was at “The Daily Show” with Trevor Noah for a few years. Before that I was at CNN. It’s a long, very diverse set of places I've worked.

I decided to go out on my own because I was kind of just bored of being in the mainstream. It was before October 7th that I was feeling quite a pull out of it. Not that I didn’t love where I worked—every place I worked, my relationships were good. I didn't have any bad experiences. It was just that after a few years at shows—it's just intense, because of the daily news. It was a ton of work and stress.

So, I was ready to try to be independent and go down the social media route. Then October 7th happened, which was crazy because it sort of gave me the story that gave me a voice online. I already had a voice online—I've done stuff in the Middle East, I've done a lot of queer things, and mixed them often—but the attacks and the subsequent genocide has been a story that means that everybody's now paying attention to the things I was paying attention to.

From the beginning, I have had my sources in Palestine, and I just got in touch with them. They have kind of led my reporting. A lot of my reporting has been repurposing reporting that's not even mine, and just giving it voice that’s kind of consumable. A lot of times written reports are very—I feel like nowadays people aren't reading as much. I would repurpose reports, give people updates, and then sort of connect dots and give my take.

I had sources that were straight, mostly. But as I gained a following, queer people started reaching out to me from Palestine through my queer friends in the Middle East.

You know, I've gone to Beirut, I've lived there, and I have a lot of friends in the Middle East who are queer, but not necessarily in Gaza. There have been more, but this conversation [in Queer Palestine] is with just two people. They're both anonymous, for the most part. As anonymous as, like, loud queer Arabs can be anonymous, which is not very anonymous.

One of them, [named QFG in the book,] I helped evacuate to Cairo. He got in touch with me in February through a friend I had met at a wedding: A gay Lebanese guy. He's like, “Afeef, there's this guy, he needs help. He's freaking out.” I think a lot of people were doing this, at the time: They were just trying to help people. They're still doing that, but this was at the height of when evacuations were really happening still, which they are not right now.

So, I talked to this person every day for three months during the genocide, while he was there. He had a harrowing story. He lost a lot of family members. He ended up finding himself alone in a tent in Rafah and somehow got in touch with me and we talked every day. Most of my role was being, I think, just a therapist, honestly. I'm documenting him as a journalist and making it clear that I'm a journalist but that I really want to help him. Because the documentation purposes are important to me, but in this level of treachery and extreme urgency it's like: Who cares? Let's just do whatever we can do to get you out.

He had lost his boyfriend in the bombing in, I think, late October, and then gone through many different kinds of harrowing things, near death experiences. He eventually found himself migrating south with everybody because of evacuation orders. He found a tent. He was very suspicious because he was a young single male. And also getting him out was very hard because he was a single male.

And then, eventually, whatever flag was on his name was lifted. Or, I don't think it was lifted—I just think he was a single man, and it was really hard to get single men out. Eventually, after lobbying and going to Cairo and getting people to advocate for him in Cairo at a travel agency and get some money out of the GoFundMe through Western Union, one day—after weeks and weeks of checking these lists of pages of Arabic names—his name appeared, and he was finally set to go. And this was all really hard on his mental health. I mean, he would send me voice notes of buzzing drones. Finally he got on a bus, passed through two halls, one Palestinian, then one Egyptian, and he got on a bus to Cairo.

I set him up with some friends who brought him food and got him an AirBnB. He's in Cairo, and he was estranged from his mother and his brother. They hadn't spoken in years because he was queer and they kicked him out. But then he found out that they were alive and he was adamant on trying to get them to escape, too. So, he coordinated with them and got them out as well. And now they're in Cairo as well. He's living a queer life in Cairo. I mean, he's dealing with a lot of trauma. A lot of trauma. Joy, obviously; he's safe. There's a lot of PTSD. It's not an easy place to be. That’s one guy.

Then there's another person who's still in the north of Gaza now. He's HIV-positive and has only so many weeks left of his medication; I think probably around eight weeks. We're trying to set him up but it’s really hard to figure out how to get HIV medication within Gaza right now. There are different organizations that I know he's now in touch with. He has, over the years, developed neurological problems because, well, it’s controversial to have HIV in Gaza, obviously. So there have been pockets of time that he has not gotten medicated, which has debilitated him.

I got in touch with Safebow, which was a temporary queer evacuation organization led by queer femme people around the world. It wasn't an NGO quite, it's hard to explain what it was. It was just a bunch of different kinds of people. They helped me to coordinate the money, because this person was online, trying to get money. He got money from different people, put it in the GoFundMe, and someone managed that GoFundMe. I did some stories on him, trying to get people to donate, just by amplifying his story. I called him “my queer friend in Gaza.”

He's extremely spiritual and a really interesting, artsy person and very cool to talk to. They both are, in different ways, very highly educated, and probably pretty privileged, relatively, because of the fact that they speak really good English and they got in touch with me and had the wherewithal to understand how to communicate with a queer New Yorker. They have their own resources to figure that out.

This person, who I call ES, is still in Gaza. I’m trying to set them up with physical therapists that can talk to them via video to try to alleviate some of their pain, because I know that the stress of genocide is making a lot of their body pains a little bit more intense.

So, that’s these two people, and there are others for sure that have been evacuated into Cairo. And there are different kinds of people still in Gaza who are queer, who have varying levels of hardship because of their queerness. I know that QFG, the first person I was talking about, while he was kicked out of his family for being queer, was adopted by another family, by his boyfriend's family. So, there is that nuance where, you know, just like every other place, some people are homophobic and some people aren't. That's mostly it.

JL: While reading the book, I was taken by how expressive ES is in their diction. The two have obviously different personalities. I noticed both of them mentioned that despite having contact with other queer people in their relationships, they didn’t “know” other gay or queer people, socially. But obviously there are two of them, and logically many other people exist who are queer. How does that speak to this media orthodoxy that a Palestinian queer culture is a contradiction in terms?

AN: Yeah, it's just made up, right? We already know everything. Like, we know what society can be like anywhere. One of them had a lot of queer relationships, or not a lot, but they knew women that were queer, knew men that were queer. Then the other one, who had traveled abroad, found his queerness abroad and then came back to Gaza, because they didn't have that many friends. So he didn't know anybody queer, but he told me about a story where he went to the market and was like, that guy's clearly gay.

It’s a war torn area, and it's just so dystopic because, it's like, the problem is the war. The occupation. The apartheid. None of these things that are joyful in life can even develop, or— not none of them, but they are so underdeveloped because everyone is traumatized at all times. And I think that that's hard for the West to really fathom. And so we try to narrativize it in another way.

People think, Oh, it's just inherent to them that they're homophobic. It's like, no, there are literally people in Hamas and in the Palestinian Islamic Jihad who are queer. They might not be loud and queer or really proud of their queerness as their first identity. A lot of people are just mothers, sons. That's their first identity. You know what I mean? Not queer first.

Like, we're queer first because it's cool and it's fun and it's interesting and we've made it so colorful here, and it's so capitalist, and it's sort of a way of being as an identity marker. But people are queer there and that's not the biggest part of their identity.

JL: Queer social life has obviously become a big part of Israeli tourism advertising over the past, I guess, decade or two. This is obviously a huge topic, but the idea that an open queer or gay social life is something that belongs to Israel is something that has been very consciously instrumentalized by the U.S., by Israel's allies. It seems really important to tackle that as a messaging point. Does this project fit into that for you, or is that too simple?

AN: Well, I kind of think that Arabs and Muslims should take a cue and really weaponize the hell out of our own queerness. That's the actual thing that they've done against us. And I think that, because we're not Western-oriented, that we haven't weaponized queerness in the same way that Westerners can weaponize it: To be victims sometimes, to be the open, cool ones sometimes.

And I think that, honestly—I don't think that we should use it as a weapon. But I think that there are just as many queer people in the Arab and Muslim world as there are anywhere else. I think it's just that we weaponize other things, like our anger and our resistance and our righteousness and our purity sometimes, which all of a sudden becomes Israel being queerer than the Arab world. But we just use different ways to be at war. I think that the Middle East is really so complicated, and the Arab-Israeli conflict, while it is a very large story, there's other stories, you know? And there are other wars.

The way that it fits in with me is that capitalism is a weapon. It can very much co-opt queerness into a weapon. And it's smart, honestly, because it works for Israel, right? There's a lot of tourism that happens, and then there's a lot of lying that happens. Like, look at us, we're quite different! We're the only places to be safe. And it's like, not really, because obviously, if you're a queer Palestinian, you're not getting killed by your community; it’s Israel.

However, as an Arab who is queer, I won't pull back from saying to my own community that we need to be more open. We need to be more challenging. We need to protect our queer people just as much as we would protect everyone else. I'm very comfortable criticizing Lebanese culture. I won’t criticize Palestinian culture merely because I'm just not Palestinian, but I can criticize Arab culture and say that we need to be less crazy about this issue, we need to be less crazy about sexual mores in general. We need to be less intense and aggressive and puritanical about these things. I'm willing to stand on that as much as I'm willing to stand on saying Israel is genocidal. There's more to say than a binary, you know, being binary is very limiting and reductive.

JL: Absolutely. I hate to center the United States in this, but this particular kind of propaganda point has been extremely effective. Random actors popping up to say, Oh, you queer protesters, XYZ. You posted recently about the Arab and Muslim votes in swing states like Michigan and Arizona in the United States. It seems like having some clarity on these propaganda points is going to be really important for people who live in the United States over the next year or so. Is there anything you want to say about the obfuscation that's going on, the misunderstandings that are swirling in American popular culture?

AN: I do think that it's ultimately about equality and access to rights and access to medical health care and access to freedoms. Who cares who wants to love whom, who cares about any of the types of ways you might live your life? If we can't all access healthcare that makes us literally safe and healthy, then what is the point of calling ourselves a free country? Good luck. If trans people need a certain amount of things at a doctor's office, or a woman who wants an abortion, or a person who has a heart disease—I have a heart disease—if we don't have what we need to feel safe in the world, then the country is not a free place.

And so we should push ourselves to think about it from that perspective at all times, not from a place of identity politics. Like, it doesn't matter where you're at in your transition, because we're all transitioning in every way. For instance, trans people are such a personification of the human perspective. We're all transitioning spiritually, or intellectually, or emotionally, and trans people are also transitioning literally physically, and so we can see their transition. They need support in that transition, in the same way we might transition in any other way. And so it's just interesting to think that we can weaponize the differences between people, and really we all need the same things: healthcare, education, places to sleep, ways to eat, cheap prices, things to keep our lives on track and normal and safe.

I think that we get too complicated when we move the conversation away from the fact that a country that is free provides certain things, and if they don't provide that, then it's not a free country. So we might as well use that phrase.

JL: On the healthcare issue, I was very struck by how ES, in their interview, spoke about how badly they want to know whether in Cairo they would be able to access their medication. There may be a lot of peril in one place, but there is some access to medication. That kind of planning or practical consideration for the immediate future is much more complex than one might guess.

AN: Yeah, totally. People with HIV in Cairo can get their medication just as easily as anyone here. It's really this interesting bubble of information, right? Like, someone who's Palestinian in Cairo is going to be very low class. I'm not speaking about their class in Palestine, but about how they're now suddenly refugees. So, they don't have citizenship, they don't have a home.

I think we really feel that in the United States, too. You know, your insurance changes and suddenly everything's expensive and you're like, what the hell? We understand these things. And we try so hard to make things that we do understand, kind of complicated. But it's like, no; a person who's an Egyptian citizen who has family money—not even like a lot, just enough to have been educated and gone to school—is going to be able to navigate the systems of corruption and play within the game more fluidly than someone who is new to the country who barely making it, who is living in a very inexpensive place, for whom it's very hard to make rent.

It becomes a class issue. And that class issue exists everywhere. Because in the Middle East—not in every place, I'm not going to speak generally—but for instance in Lebanon, the market is actually capitalism gone wrong. It’s an incredible capitalism. If you're rich, you have everything, and if you're poor, you have nothing. The rich eat everything up. They have extreme privilege, they can do whatever they want in the jungle of this place that has a rule of law that's seemingly really just targeting Syrian refugees at all times, and not, you know, anything else.

So, you're operating within a system. Whatever the system is, if you have privilege within the system, you're fine. If you're queer, it doesn't mean you're completely outside of privilege, right? You can be a rich queer person. In fact, there are royal people who are queer. And we don't know about them, but you know, we do—they exist.

JL: You've been working extremely hard, it seems.Thank you so much for doing these interviews. It's a great privilege to be able to read them. Um, how are you?

AN: Good question. Stronger than I've ever been, probably, but also extremely sad and sometimes just pissed off and frustrated. But also strong, because I think with this kind of work you learn what capacity is, and what it takes to step away for a second, lean on the people you love, be thankful for the things you have. Nothing is harder than what's in your brain.

These people that I'm talking to are incredible, super-heroic versions of all of us. They're being called to find their extreme capacity. And so I am thankful to have witnessed them, because it has made my capacity grow. I hope that as we all learn more in general about people who are fighting for their lives that our capacity continues to grow because what it really is is about empathy and education.

It's just trying really hard for other people for no reason except for the intuition that maybe the only thing that really makes you feel good at all is helping other people. And I think, you know, I'm fine. I'm surviving and I'm happy. I have an easy life in New York City. I'm a gay man in New York City. There couldn't be an easier life.

JL: You've articulated things in a way that's extremely helpful. As people working in the media, it does seem to me that there's a great deal of fear and self-interest going on amongst professionals. Our colleagues are thinking, what can I not say because I need to protect myself? So, I value your and Pinko’s contribution in terms of it being words written down that I can help publicize, because people are very, very curious. There's a great need for—well, content is a stupid way to put it, but the written word. People are desperate to consume other people's personal perspectives in this way.

AN: I mean, we're all working together to just do our best to, I don't know, be there for each other in the ways that we can. We all have our role in this crumbling of empire, or at least in challenging it. That's what we're here for.

Purchase your copy of Queer Palestine here.

Comments ()